Performance, painting, and the therapeutic function of art

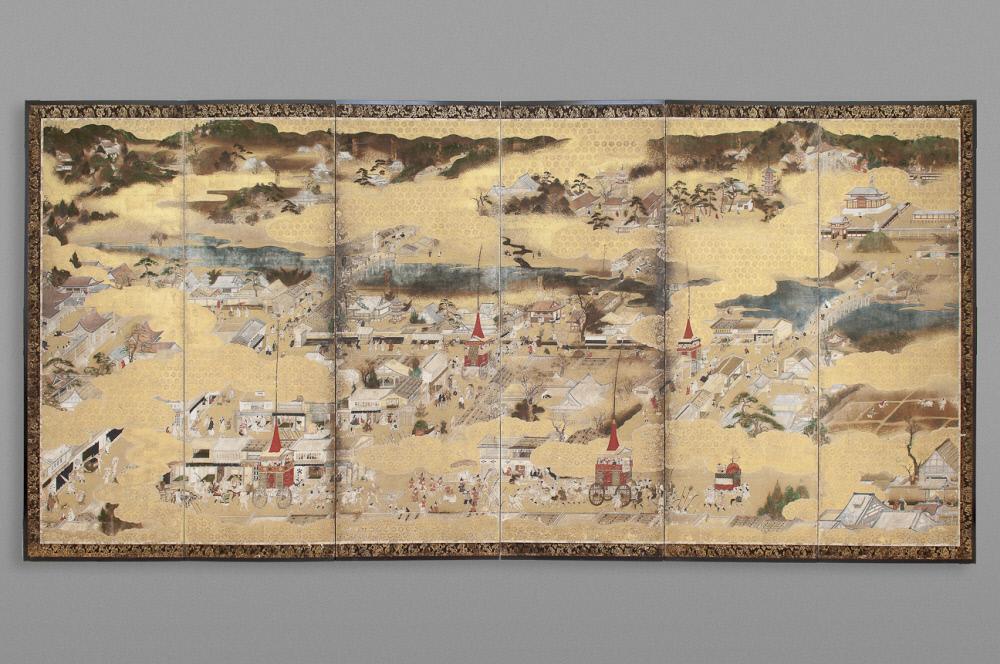

Among the works of Japanese art that Anna Rice Cooke added to the Honolulu Museum’s collection during its early years is a pair of folding screens that depicts Kyoto from a bird’s-eye view. Viewers enjoy this highlight of our museum’s collection for various reasons. The golden clouds, which span the entire composition, and between which colorful vignettes in the city are visible, display extraordinary craftsmanship. The view is also so cartographically accurate that viewers familiar with the city can identify historical landmarks such as the Golden Pavilion. Dating to the 1610s, Scenes in and Around the Capital is a rendition of a popular painting theme that originated in the early 16th century, before the military government moved the capital to Edo (modern-day Tokyo). Each iteration of this painting theme depicts Kyoto in a unique way, and what seems particularly worthy of attention at this moment is the story that underlies this particular rendition.

Anonymous

Scenes In and Around the Capital, right screen

Japan, Edo period (1615–1868), c. 1611–1615

One of a pair of folding screens; ink, color, and gold on paper

Gift of Anna Rice Cooke, 1932 (3454)

Anonymous, Scenes In and Around the Capital, right screen, Japan, Edo period (1615–1868), c. 1611–1615, One of a pair of folding screens; ink, color, and gold on paper, Gift of Anna Rice Cooke, 1932 (3454)

If you look carefully, you can see groups of revelers parading down the streets, beginning at Kiyomizu Temple in the upper right corner of the right screen and traversing the city until they reach the entrance to Nijō Castle in the center of the left screen. Some of the folks are dressed in historical, military uniforms, and among them are enormous, wheeled floats (yamaboko) topped with bright red towers that rise to spectacular heights. This procession is the Gion Matsuri, one of Japan’s most famous festivals, which originated in 869. The function of the festival at that time was to purify Kyoto from an epidemic. Though we have no details about the pestilence, in light of the city’s extreme summer heat and humidity, in combination with the lack of modern sanitation at that time, outbreaks of cholera, malaria, and dysentery were not uncommon. Emperor Seiwa, who ruled Japan from 858 through 876, however, believed the illness was caused by angry gods (goryō). To appease those spirits, he ordered the construction of sixty-six floats, each crowned with a tall spear or flag, which were navigated through the streets as a purification ritual. In 970, the parade became an annual event held in the latter half of July.

Over the following centuries, the Gion Matsuri evolved in intriguing ways. In order to flaunt their wealth and to express their support for the community, the city’s kimono merchants funded the construction of the floats, whose decorations grew larger and increasingly extravagant over time. Contemporary floats can tower up to 88 feet high and weigh more than 13 tons. In 1979, Japan’s Agency of Cultural Affairs designated these structures as Important Intangible Folk Cultural Properties, and in 2009, UNESCO included the yamaboko in its Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity. Over time, these artworks and the performances in which they are presented to the public have been disassociated with ideas of spiritual and physical purification. Although this year’s festival has been cancelled due to the difficulty of ensuring proper social distance for participants, perhaps the next Gion Matsuri will be an opportunity to further reflect upon the festival’s original purpose.

– Stephen Salel, Robert F. Lange Foundation Curator of Japanese Art