The Art Historical Precedents of Modern Japanese Comics, Part 1 of 5: Giga

Recent exhibitions about modern Japanese comics (manga) at the Honolulu Museum of Art merit a discussion about how examples of traditional Japanese art in the museum’s collection serve as precedents for such artwork. As mentioned in the introduction of those exhibitions, numerous similarities connect modern comics with Japanese woodblock prints, of which our museum has amassed a world-renowned collection. Like manga, woodblock prints were produced in large print runs and intended as visual entertainment for the common people. Moreover, just as ukiyo-e inspired European painters over the past 150 years, manga and non-Japanese comics are likewise influencing contemporary visual culture (particularly the medium of film) throughout the world in equally dramatic ways. It is not surprising, therefore, that, as witnessed in recent exhibitions at the British Museum and our own institution, both scholars and the general public have accepted manga as a vibrant form of contemporary fine art.

In this and subsequent blog posts, a variety of Japanese terms will be used to distinguish the diverse traditions in the history of painting and printmaking from which Japanese comic artists of the early 20th century drew inspiration. These labels include haiga (illustrations of haikai poetry), Ōtsu-e (“pictures from Ōtsu City”), and manga (in its original meaning). In order to avoid confusion, some important English terms also deserve clarification. The word “cartoon” describes a simply executed sketch or collection of sketches. The label “comics,” on the other hand, denotes a series of images, often combined with text, that conveys a narrative in a single-sheet or multi-page format.

Manga 1

Attr. Tosa Mitsunobu (1434–1525). Copy of the Frolicking Animals Handscroll, detail. Japan, Muromachi period (1336–1573), 15th–early 16th century. Handscroll; Ink and color on paper. Gifts of the Robert Allerton Fund, 1954 (1951.1) and Jiro Yamanaka, 1956 (2212.1)

One of the oldest traditions in the history of Japanese art that displays clear aesthetic connections to modern Japanese cartoons and comics is giga (literally, “humorous pictures”), and the most celebrated artwork in that genre is The Handscroll of Frolicking Animals and Humans (Chōjū jinbutsu giga emaki, 12th–13th century), a set of four picture scrolls attributed to the Buddhist priest Kakuyū (1053–1140, known also as Toba Sōjō) and owned by Kōsanji Temple in Kyoto. Designated collectively as a National Treasure in 1952, the scrolls and their fragments are entrusted to several museums throughout Japan. A few hand-painted copies have been produced, and the Honolulu Museum of Art owns a 15th–early 16th century reproduction of the first scroll attributed to the painter Tosa Mitsunobu (1434–1525).

Populated by anthropomorphized frogs, rabbits, monkeys, cats, and foxes, as well as relatively naturalistic deer, snakes, and wild boars, the first scroll is unquestionably the most famous. This work of giga expresses a wide variety of comedic styles. Examples of endearing slapstick can be found in scenes of the rabbits and frogs wrestling one another, while images of the frogs and monkeys performing Buddhist rituals exude a sense of caustic social satire. These latter vignettes culminate with the view of a frog posing like a statue of the Buddha himself, seated in lotus position upon a dais and backed by a large leaf in place of a luminous mandorla. Kneeling in front of the frog, a monkey priest is depicted chanting sutras.

The fame of the Frolicking Animals Handscroll, as it is alternatively called, has only increased over time. Film director Isao Takahata (1935–2018) cited this artwork as the first known example of Japanese comics. In turn, critics such as Ōtsuka Eiji (born 1958) have retorted that the scroll relates to modern manga only in minor, superficial ways and that much more obvious art historical influence can be found in Euro-American precedents such as the work of Walt Disney.

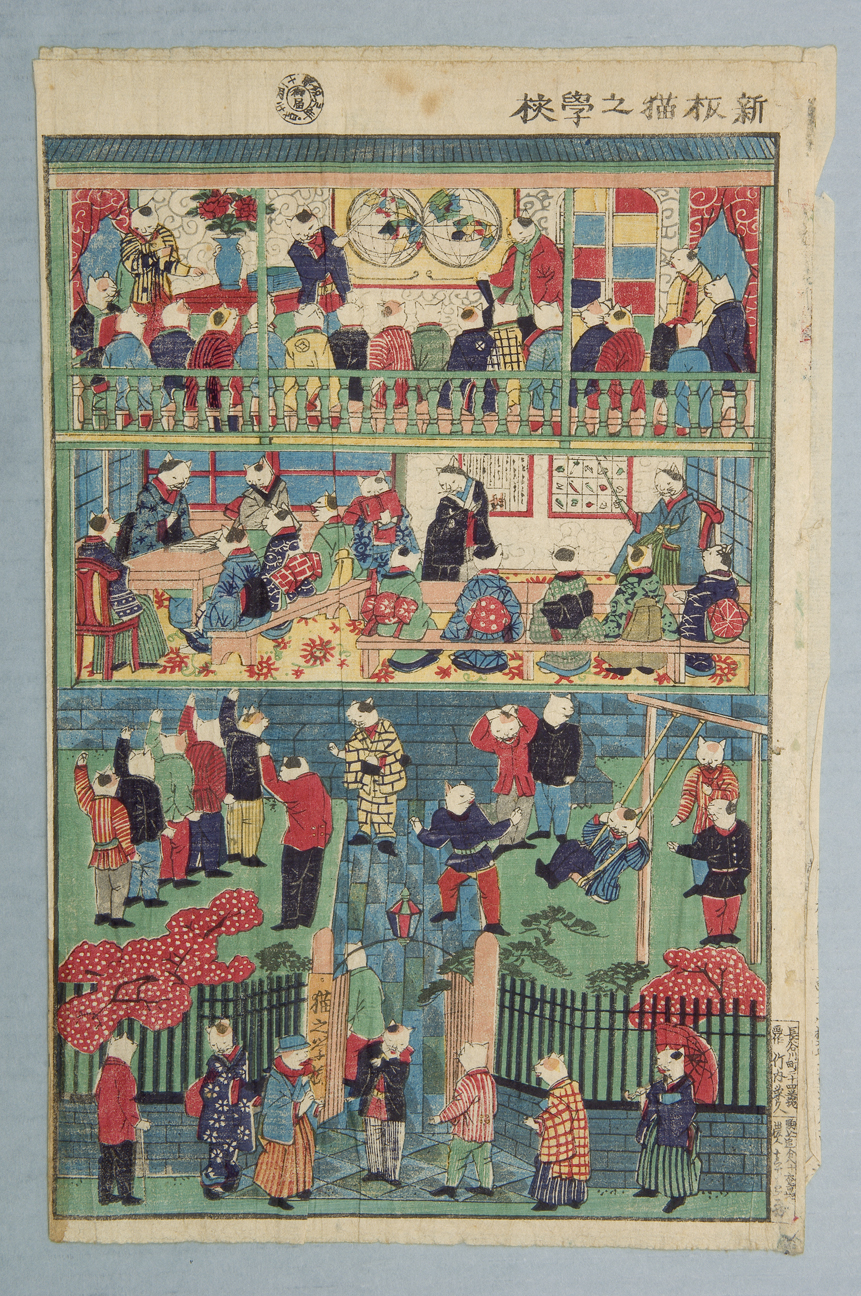

School for Cats

Utagawa Kunisada III / Kunimasa IV (1848–1920). School for Cats. Meiji period (1868–1912), 1876. Woodblock print; ink and color on paper. Gift of Oliver Statler, 2003 (29212)

A slightly more conciliatory approach to this debate would be the recognition that, like the cue ball in a game of pool, the Frolicking Animals Handscroll may have exerted an indirect yet substantial effect upon modern manga through a constellation of stylistic influences spread throughout the history of Japanese art. For example, as will be discussed further in an upcoming blog post, an 18th-century style of figurative painting that exaggerated body proportions and gestures to hilarious extremes was dubbed Toba-e (literally, “pictures of Toba”) in recognition of the scroll’s supposed creator, Toba Sōjō. In the 19th century, likewise, several print designers revived the tradition of giga. Works by Utagawa Kuniyoshi (1797–1861) including images of cats dressed in kimono and those of goldfish walking on their hind fins, are particularly well remembered, Others, such as School for Cats (1876) by Utagawa Kunisada III / Kunimasa IV (1848–1920), have been largely forgotten, but as crucial evidence of how the aesthetics of modern manga developed over the span of several centuries, they deserve a great deal of recognition.

– Stephen Salel, Curator of Japanese Art