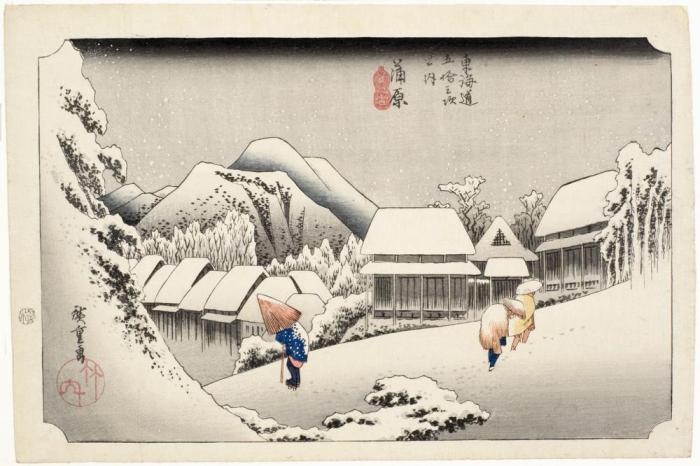

Hiroshige’s "Night Snow at Kambara"

The holidays always bring a sense of nostalgia for winter nights spent gathering around the fire with friends and family over warm food and even warmer drinks. This is true even in Hawai‘i. Although most of us are probably happy to exchange blizzard season for whale season, when Shaka Santa and Tūtū Mele arrive in front of Honolulu Hale—appropriately donning COVID masks this year—our thoughts still turn to snow.

One of the most perfect expressions of snow ever accomplished in the arts is Utagawa Hiroshige’s Night Snow at Kambara. Somewhat ironically, the finest surviving impression of this print is at HoMA, as far away from actual snow as one can get. Still, HoMA makes perfect sense as a home for Kambara. Thanks to famous novelist James Michener (1907–1997), who worked with the museum for nearly four decades to build a print collection celebrating the Japanese-American community in Hawai‘i, HoMA has, among many other distinguished achievements, the largest number of works by Hiroshige in any public institution. Another irony: while Michener admired Hiroshige at his finest—Kambara in particular—he also disparaged him for over-producing mediocre designs just to make money, so the world’s largest Hiroshige collection was donated to the museum by someone who was decidedly not a fan of the artist.

15927

Utagawa Hiroshige (1797–1858), Night Snow at Kambara, Japan, Edo period, c. 1833–1834. Woodblock print; ink and color on paper. Gift of James A. Michener, 1971 (15927)

Kambara depicts a quiet scene, and its strength lies in its stillness. This makes for an interesting comparison with another of HoMA’s prints that has recently received considerable attention, Hokusai’s Great Wave Off Kanagawa. Together, these two prints are Japanese art’s ambassadors, universally recognized and celebrated around the world. Great Wave is overflowing with energy and excitement, as small boats are tossed about in a roiling ocean, with tiny Mount Fuji (the actual subject of the print) just visible in the distance. On the other hand, there is almost no movement in Kambara, except for the crunching footsteps of three lonely travelers trudging towards what one hopes will be a warm room for the night.

Outside Japan, Great Wave has perhaps attained more renown, and is ubiquitous in everything from bumper stickers and emojis to Godzilla t-shirts. If one were to ask art historians and aficionados which one they preferred, though, most would likely say that Kambara better represents the unique Japanese aesthetic of wabi—literally “Japanese beauty”— the nostalgic, melancholy expression of a perfect moment of fleeting beauty within the everyday transitory world. Hokusai was a master of line; Hiroshige was a master of light and atmosphere. The secret to his success with Kambara has to do with light. But wait, you might say: “there is no light. All of the houses are dark, the doors are shuttered, there is not even a sliver of new moon.” “Yes, exactly,” Hiroshige would reply. “And yet, there is still light.” The white blanket provides a crystalline clarity to the atmosphere, in which the snow itself seems to glow with an inner radiance.

– Shawn Eichman, Curator of Asian Art