"Others: The Depiction of Foreigners in Japanese Prints": images from an era of isolation

There’s no question the profound impact that COVID-19 has had on our ability to scratch our travel itch. But imagine for a moment that you never once left your country, state or hometown in your lifetime, and equally, that outside travelers were not allowed in. How would isolationism of that magnitude shape perceptions around that which we do not know? Others: The Depiction of Foreigners in Japanese Prints, currently on view in the Robert F. Lange Gallery, mark in time the before-and-after of Japan’s more than 200-year period of deliberate isolation. The ukiyo-e on view depict the external world through a Japanese lens, offering us unique insight on perceptions of foreign cultures during that period.

In 1635, shogun Tokugawa Iemitsu promulgated the Sakoku Edict in order to politically unify the Japanese archipelago and eliminate the influence of other nations. This edict forbade Japanese citizens from leaving the country, outlawed the practice of Christianity, and restricted trade to Chinese, Dutch, and Korean merchants to a limited number of ports within Nagasaki. Because of this policy, very little art, literature, or technology from the rest of world entered Japan and there were very few non-Japanese people in the archipelago.

But, as Stephen Salel, HoMA’s Curator of Japanese Art emphasizes, “There’s nothing more enticing than something you can’t have. These prints demonstrate that although the country’s policy was to resist cross-cultural interaction, these encounters were happening nonetheless.”

Japan’s policy of isolationism continued until 1854, when Commodore Matthew Perry (1794–1858) of the US Navy anchored his ships off the coast of Kanagawa. Perry initiated a series of negotiations with the Japanese government that ultimately culminated in the Harris Treaty of 1858, which required Japan to reopen all of its ports to international trade.

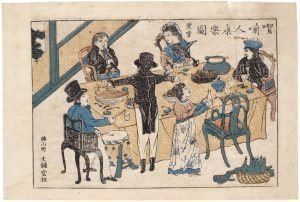

Depictions of foreigners in Japanese prints—including both Nagasaki-e (pictures from Nagasaki) produced during the isolationist era as well as Yokohama-e (scenes from Yokohama) produced from 1858 until the 1880s—were intended to satisfy Japanese viewers’ curiosity about other cultures.

tw

Unidentified Artist, “Dutch Group Having a Quiet Party”, Japan, Edo period (1615–1868), c. 1800. Woodblock print; ink and color on paper. Gift of Louise Bachmeyer in memory of Karl Heinz, 1987 (19805)

“Also of note, these pieces in a sense can be seen as the Japanese equivalent of what was happening concurrently with Western art in the 19th century,” adds Salel. “For example, the Impressionists were inspired by Asian art, particularly Japanese art, but, didn’t really understand it closely. In a similar way, these prints demonstrate Japanese artists’ admiration of other cultures while still maintaining a sense of distance.”

The prints in Others not only offer us a look into the ways in which different nationalities were perceived within that insular social environment, they also remind us of the benefits of cross-cultural understanding within our own communities.