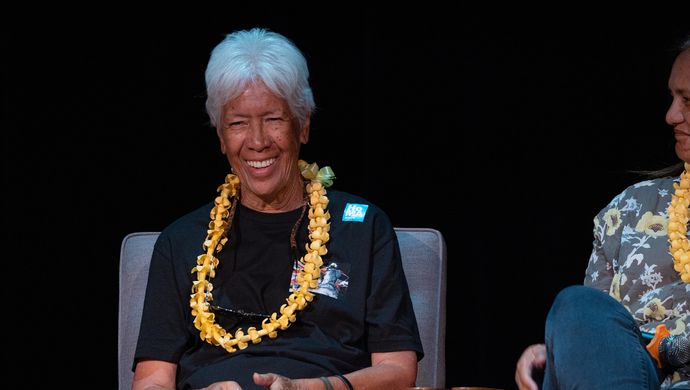

HT25 at HoMA: Al Lagunero creates pilina through art

“Tūtū and the family would travel from Kona to Hilo. Arriving at Volcano sometimes it wasn’t very clear—either vog or mist was present,” recounts Lagunero in his sonorous voice. “The family says that when this happened, tūtū would get out of the car and start to oli, and then the place clears, and she lifts her palm to the wind and on her palm Pele’s hair falls. Pele’s hair is glass shards, long pieces that look like golden hair, and in her hand it doesn’t break. As a child this story really stays with you.”

All these years later Lagunero has interpreted the story on canvas for the Triennial. Talking with the artist is to have time collapse—past generations are present and distant history feels like yesterday. He created his Triennial paintings during a residency at the Mānoa Heritage Center last fall, the result of a chain of events that illustrate how kismet can sometime play a crucial role in curation.

While doing a site visit at Mānoa Heritage Center in December 2022, Triennial co-curators Wassan Al-Khudhairi and Noelle Kahanu learned how Charles Montague Cooke Jr., who built the property’s Tudor-style mansion Kuali‘i, was born prematurely to Anna Rice Cooke, and was saved by Ka‘aha‘āina-a-ka-haku Naihe.

Shortly after, the curators went to Maui and visited Lagunero, who shared the same story. “Wassan instantly made the connection,” says Kahanu, “and from there, it was a natural step to see if Mānoa Heritage Center would consider an artist residency and whether Al would consider residing on Oʻahu for a time.” Both enthusiastically agreed and in fall 2024, Lagunero spent two weeks painting at Mānoa Heritage Center in a studio set up on the lanai of the property’s Hogan House.

Connection to place

The four paintings on view are part of the series “Keauhou,” which means “the new era.” “I come from that area,” explains Lagunero. “Tūtū’s work and her background resonated with me—the whole family lineage, the meaning of her name, and what it documents in the transitions of Hawai‘i.”

When Ka‘aha‘āina-o-ka-haku Naihe was born, says Lagunero, “the first holy communion was given in Kailua in a church built by missionaries. Her name means ‘the Lord’s supper.’ So it is a real document of the great changes of that time.” He recounts how King Kamehameha III was born in a cave in Keauhou and went on to introduce the Great Mahele in 1848—when the traditional ahupua‘a system was replaced by the western concept of land ownership.

“Can you imagine the great change where people have previously not had that?” says Lagunero, and his eyes start to well up. “It brings great tears to find out that many of these people who were given lands that were volcanic had to scrape to get by and plant things. That’s a great, great emotional change. People don’t know the tortures, the things that went on to get people to sign their name with an X on the line. To this day, money is not really an easy concept for Hawaiian people to understand. We mostly give a lot of ourselves and give things away.”

While working at Mānoa Heritage Center, Lagunero says, “the winds were very playful,” as they were in the scene his painting Ka‘aha‘āinaokahaku depicts. When asked about his process, he replies, “It’s very na‘au oriented,” meaning instinctual, or coming from the heart or mind. He also finds inspiration in hula, “the rhythm, the respect for how the sounds move over us.”

The painting Red Scarf is a nod to the story of Princess Ruth, a great-granddaughter of Kamehameha I, who traveled from Honolulu to Hilo in 1881 when a lava flow from Mauna Loa threatened the town. “She goes in a buggy and presents her red scarf and the flow does not go down to Hilo,” says Lagunero. “I’ve had experience with red scarf and Pele’s messages. She’s very active still. She also wants to be known as the woman of compassion, different from the woman of destruction that popular literature has made her out to be. I do these under the authority of the One.” The artist points out that four days after he completed the painting, Kīlauea erupted.

Also on view is a sister work called White Scarf, illustrating a time when Lagunero performed a prayer in Ka‘ūpūlehu, on the rugged west coast of Hawai‘i Island. “We needed to go to a certain spot,” he explains. “As we advanced towards it, the waters were thunderous. Humungous waves were coming up to the shoreline. So I took a white scarf and placed it, along with flowers, on a stone and the ocean settled until we were finished with the prayer. As soon as it was over, the waters came crawling up to take the scarf and flowers.”

For Lagunero, these kinds of experiences are a type of technology. “There is a technology to aloha,” he says. “It’s not all this romantic stuff that people talk about. We gather things with aloha. How we prepare them is aloha. There is a process always with aloha.”

“This project exemplifies a place-based approach resulting in pilina—the formation of deep relationships—between Al, Kuali‘i, and the caring staff of Mānoa Heritage Center,” says Kahanu. “His resulting body of work was inspired by the life of Ka‘aha‘āina-o-ka-haku Naihe and Keauhou, Hawai‘i Island, marking the elemental, genealogical, geographical, political, and transformational events of her homeland of Keauhou.

“Keauhou” is on view through May 4.

Hawai‘i Triennial 2025: Aloha Nō

The triennial theme ALOHA NŌ is a call to know Hawai‘i as a place of rebirth, resilience, and resistance; a place that embraces humanity in all its complexities. You can see the work of seven more artists at HoMA, then explore ten more O‘ahu sites that feature the works of 38 other exciting artists and art collectives. And for the first time, the Triennial has expanded to Maui and Hawai‘i Island too.

Story

Story