Story

Story

Five Things to Know about Impressionist Mary Cassatt

By Antonia Smith, digital project manager, Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco

This internationally acclaimed exhibition was organized by the Philadelphia Museum of Art and traveled to the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco. It is the first North American retrospective of Cassatt’s work in 25 years and presents new insights into the artist’s approach. HoMA presents an essential selection of works from the show, and adds a Cassatt painting, five prints, and two drawings from its own collection, revealing how her work as been a part of the Museum’s history from the day it opened.

1. She was the only American to exhibit with the French Impressionists

Born in 1844 in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, Cassatt began her artistic training at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts at the age of 16. In 1868, her painting Mandolin Player was accepted into the Paris Salon (the official art exhibition sponsored by the French state). Settling in Paris in 1874 and becoming a regular at the Salons, Cassatt met founding Impressionist member Edgar Degas, who invited her to join this avant-garde group of French artists. She was the only American officially associated with the group, and participated in four of their eight exhibitions between 1879 and 1886.

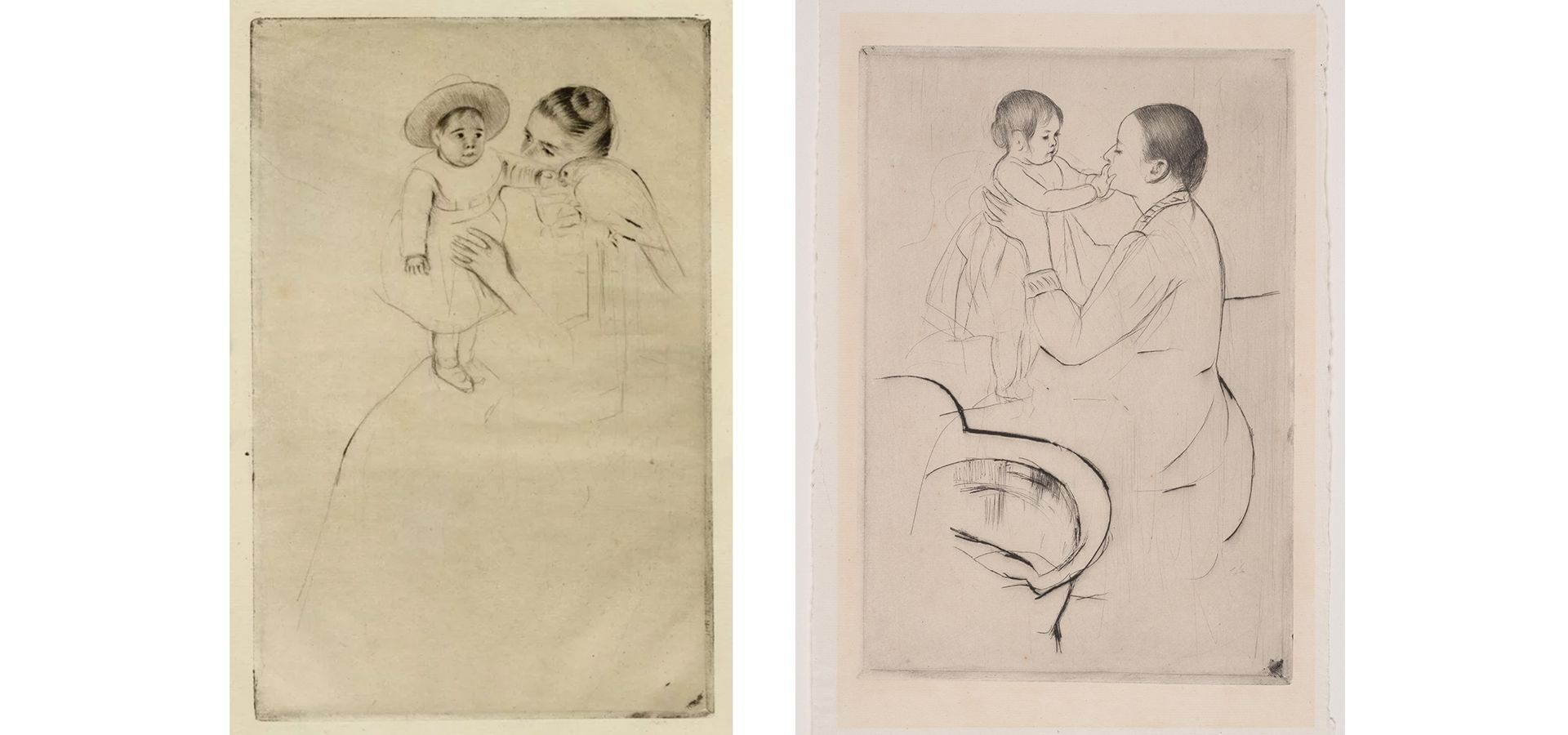

LEFT: Hélène of Septeuil, Around 1890. Drypoint on laid paper; state 4 of 4. Philadelphia Museum of Art: Gift of Mrs. Horace Binney Hare, 1956-113-8

RIGHT: Mother Marie Dressing Her Baby after the Bath, Around 1890. Drypoint with plate tone on laid paper; state 2 of 2. Philadelphia Museum of Art: Gift of Mrs. Horace Binney Hare, 1956-113-12

2. She created radical art under the cover of “feminine” subject matter

Parisian society in the late 19th century was highly divided and class-conscious. There were expectations about what a genteel woman artist like Cassatt ought to depict. Cassatt turned to subjects that were accessible and acceptable. She painted women and children in her sphere (her sister Lydia, nieces, nephews, children of friends, and the women who cared for them). Often dismissed as “sentimental,” these works were, in fact, bold and pioneering both in technique and subject matter. While mother-and-child imagery was nothing new, in Cassatt’s depictions, she emphasized the work of caretaking—the physical and psychological effort of comforting, breastfeeding, bathing, dressing, and educating children. She also highlighted the agency, intellect, and inner lives of women by showing them deeply engaged in their pursuits.

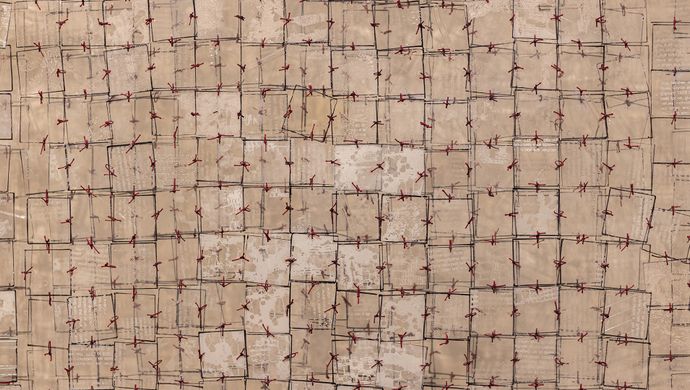

The Map, 1890. Drypoint on laid paper; state 2 of 3. Philadelphia Museum of Art: Purchased with the Joseph E. Temple Fund, 1949-89-16

3. She was a particularly innovative printmaker

Cassatt experimented across a number of media—painting, pastel, and printmaking. Some of her greatest innovations came in printmaking. In 1890, she attended an exhibition of Japanese woodblock prints and was inspired by the colors and patterns she saw. (The exhibition includes versions of some of the actual prints Cassatt saw!) Using Western techniques, Cassatt set out to produce a similar effect, pioneering a new method of printing in color on copper plates. The prints in her “Set of Ten” (1891), made using this method, are considered some of her most significant works and among the most inventive in the history of modern printmaking. On view from this set will be The Letter.

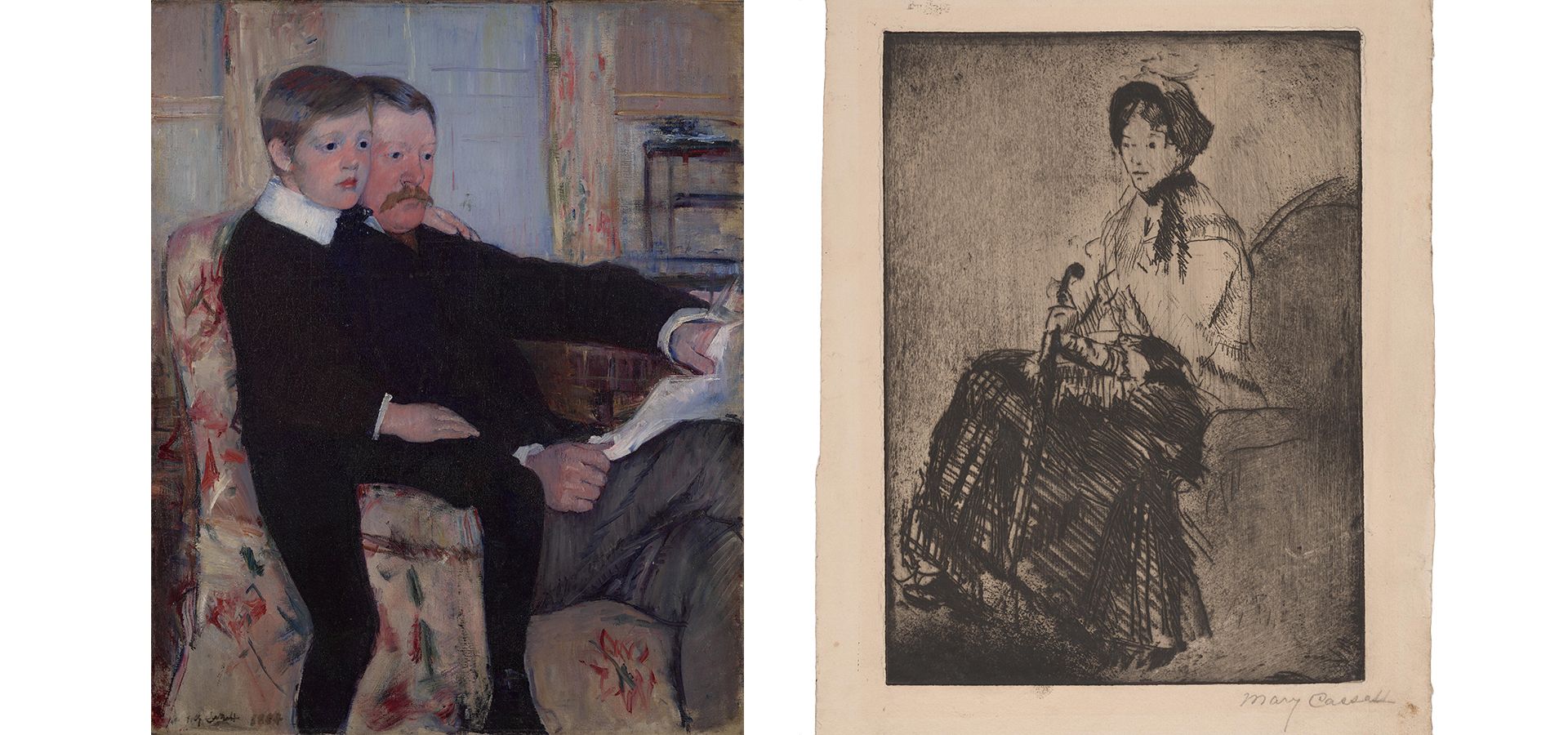

LEFT: Alexander J. Cassatt and His Son, Robert Kelso Cassatt, 1884. Oil on canvas. Philadelphia Museum of Art: Purchased with the W. P. Wilstach Fund and with funds contributed by Mrs. William Coxe Wright, W1959-1-1

RIGHT: The Umbrella, 1879.Soft-ground etching with plate tone on laid paper; state 2 of 2. Philadelphia Museum of Art: Gift of R. Sturgis Ingersoll, Frederic Ballard, Alexander Cassatt, Staunton B. Peck, and Mrs. William Potter Wear, 1946-11-6

4. She was a savvy businesswoman

Cassatt saw her artistic pursuits as a professional career. This approach went against societal norms, since professional ambition was considered a masculine virtue. Nevertheless, Cassatt was determined to become a professional artist, be taken seriously, and exhibit and sell her works. Over the course of her career, she produced approximately 380 pastels, 320 paintings, and 215 prints. In addition to participating in the art market as an artist, she also served as an advisor, helping shape public and private art collections across the United States. By the end of the 19th century, she had established a global reputation—and a growing market—for her own artwork.

Family Group Reading, 1898. Oil on canvas. Gift in memory of Wilhelmina Tenney by a group of her friends, 1953 (1845.1). Philadelphia Museum of Art: Gift of Mr. and Mrs. J. Watson Webb, 1942-102-1

5. She was an advocate for women’s rights

In the final decades of Cassatt’s life, her eyesight started to fade. She created her last works in the early 1910s, and began turning to pursuits outside of art. In 1915, she organized an exhibition with art collector and friend Louisine Havemeyer to benefit women’s suffrage. The exhibition featured approximately 20 works by Cassatt, as well as works by fellow Impressionist Degas.

Top banner

Mary Cassatt (American, 1844-1926). Woman in a Loge, 1879 (detail). Oil on canvas in a 2023 interpretation of Cassatt’s original green frame. Philadelphia Museum of Art: Charlotte Dorrance Wright Collection, 1978-1-5

Text adapted from research by Jennifer Thompson, curator of European painting and sculpture at the Philadelphia Museum of Art; Laurel Garber, assistant curator of prints and drawings at the Philadelphia Museum of Art; and Emily Beeny, chief curator of the Legion of Honor.