Honolulu artist Eduardo Joaquin and Salman Toor

HoMA sales associate Eduardo Joaquin was already a fan of the work of Salman Toor when he learned the museum would be presenting the exhibition Salman Toor: No Ordinary Love, now on view through Oct. 8. A talented painter himself who has exhibited widely in Honolulu, Joaquin included Toor (along with Cecily Brown and Jennifer Packer) in a presentation on form, content and practice he did for an Advanced Painting class as an art student at the University of Hawai‘i.

The presentation was supposed to be 20 minutes, but Joaquin took an hour. “There was so much to talk about,” he explains. “His painting practice early in his career was so rooted in Eurocentric, western tradition, it was very academic and inspired by the Old Masters. But even in those works, he was already bringing in brown figures, figures of South Asian descent, things he saw in his life, multicultural themes and Islamic subject matter, too.”

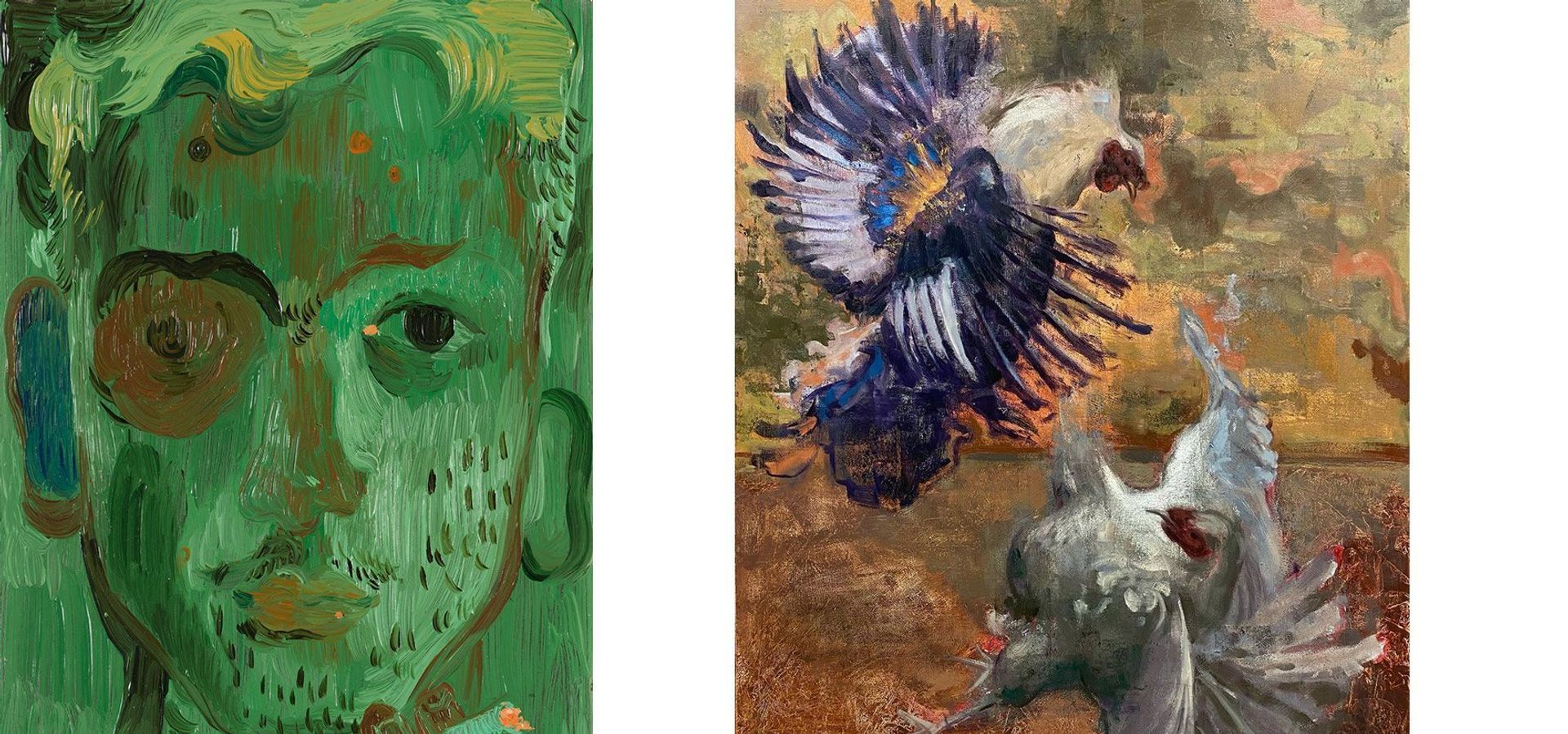

And that struck a chord with the Philippines-born, Honolulu-raised Joaquin. “That’s something I never shied away from, that academic tradition of painting,” he says. He also is exploring his heritage after feeling pressured to assimilate as a child, as can be seen in his dynamic paintings such as Sabong, which was in the inaugural MACC Biennial this past summer. “When you’re a kid, the last thing you want to do is stick out like a sore thumb, so I shed my culture. My work lately has been trying to come to terms with it.”

Meeting an art hero

As part of festivities for the opening of No Ordinary Love, exhibition partner Shangri La hosted a lunch for Toor. With the museum always looking to create opportunities for Hawai‘i artists, Learning & Engagement director Aaron Padilla invited Joaquin to attend, not knowing the young painter had been following Toor on Instagram for three years.

Joaquin was just happy the show was coming to the museum, he never imagined having lunch with Toor.

“They have that saying, never meet your heroes, but this was totally the opposite,” he says. “It really humanized [Toor’s] work in a sense. I’ve looked at his paintings hundreds of times, made a presentation on them, and analyzed them, but to speak to the person who created them really fleshed out the works for me, too.”

Joaquin was struck by Toor’s demeanor. “You felt a gentleness, soft spokenness, and such elegance and eloquence. You can feel he is passionate about painting,” he says. Toor talked about where he is at in his career, the pressures he has faced and how No Ordinary Love came to be. “He also shared a little back story on the figures in the paintings, which I thought was amazing. Very drastic shift—there’s a point in his career where he completely changed. He started making work that was very honest, genuine. Collectors expect you to pump out works that feel like you or are like what has sold, and for him to flip completely and make these imaginary scenes of his friends hanging out in New York, it felt very genuine to me and that’s something I really found refreshing in the realm of contemporary art. It felt accessible and honest, you can feel it when you view the works.”

When asked to name highlights of the exhibition, Joaquin says, “For me, I think Boy with Cigarette, just because of the scale. To have these pretty large-scale works and then have a piece so small and intimate, it forces you to come closer to it, and draws you in, especially in the context of everything else. That is one of my favorites. And the sketchbook, just to see a little of the behind-the-scenes—I love anytime there is a sketchbook or sketches in a show. For artists, it’s very valuable because you get a little bit of insight into the process and how they work. Those two were huge standouts for me. But it’s hard to pick!”

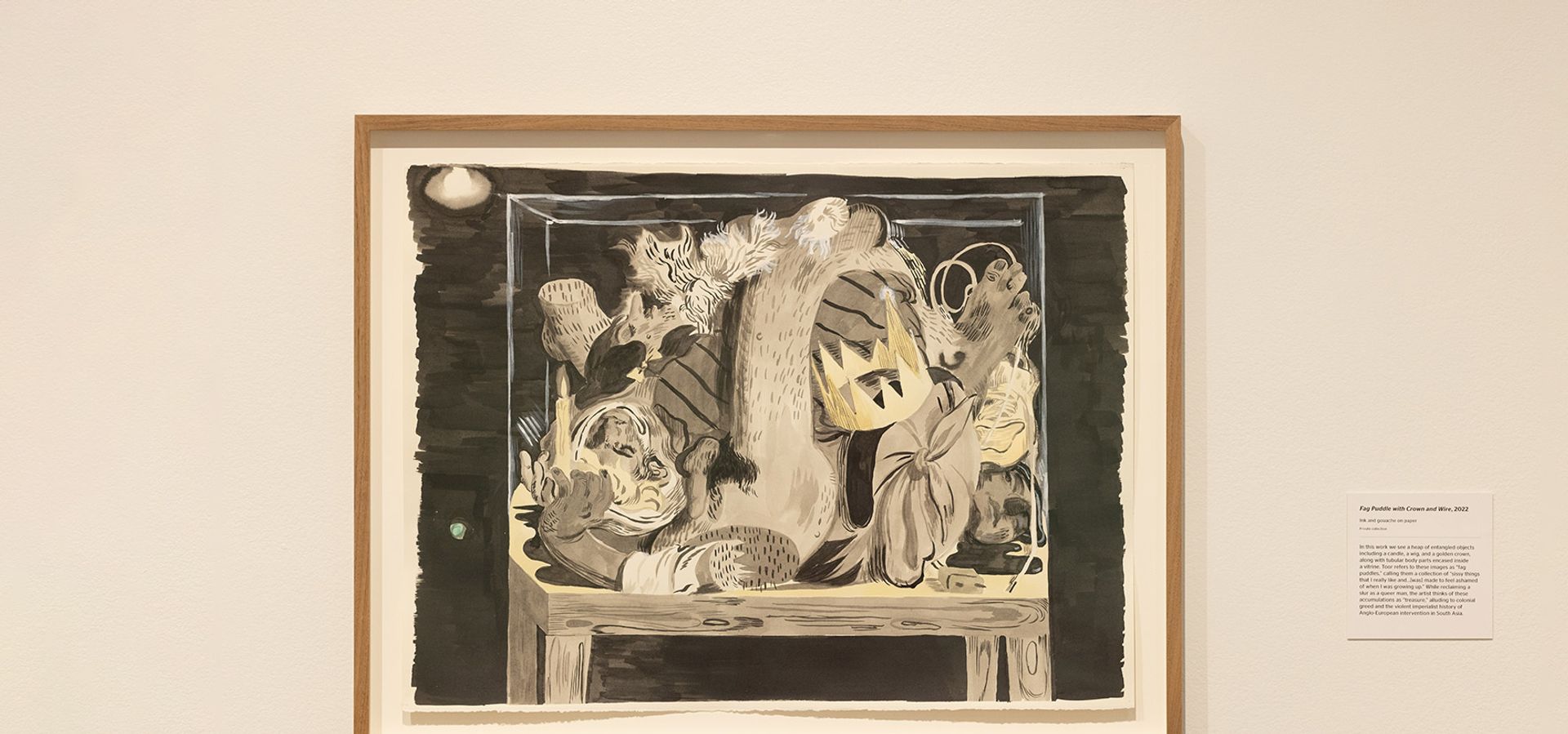

Joaquin is also drawn to Toor’s ink paintings. “It is so cool to see his brushwork, his mark making, translated into ink and drawing,” he says. “It was really interesting because it made sense. That approach to painting, the way he does it is very rooted in drawing, sort of hatching and crosshatching. For him to bring it into drawing is interesting. You can see the connection. I wonder what came first, whether he approached painting in a drawing way or took that little aspect of his paintings and brought it to drawings.”

Another aspect of Toor’s work that resonates with Joaquin are the figures going about their daily lives. “They feel contemporary. They feel like now,” he says. “They feel like people you bump into the street, people I’d help at the Museum Shop or someone I’d talk to at a bar. That’s something I love so much about art and painting. Some people like it for a sense of timelessness, classics. But I really like works that feel of a certain time. It feels amazing to see someone use this medium that is thousands of years old to root it to our time now.”

Toor talked about how many of the works in the exhibition “came out of little him,” recalls Joaquin. “Like as a young closeted queer boy in Pakistan dreaming of this imaginary world in New York where he could be free and just be with people who accept him for who he is and celebrate all the unique aspects of a community. I think that was something so beautiful to imagine, young him seeing the works he’s doing now and where he is now. That’s something I’ve always been searching for in painting—how do I make little me proud?”

Joaquin on his art and journey

Joaquin started working at the Museum Shop in February, but his relationship with HoMA goes back much further. “I’ve grown up at this museum,” he says. “This has been the go-to ever since I was a kid. I used to go on field trips here all the time. I took art classes during the summer when I was in elementary school. That was when I had my first show.”

He remembers when, as a middle school student on a HoMA field trip, he had to select a painting and write about it. “I was so torn between the Masami Teraoka, the big gold one, and Francis Bacon’s Three Studies for a Self-Portrait. Now thinking back on it, those were pretty heavyworks to pick as a young kid.”

Putting the museum in the context of access to art, Joaquin says, “Oh my god, to be able to walk into the gallery and see the big names like van Gogh and Monet! Picasso! It’s so amazing. And for me to see Lauren [Hana Chai], who is a great friend, have a museum solo show here, is really awesome. It’s such a privilege to be in this space.”

Joaquin, who recently graduated with a BFA from UH Mānoa, credits his parents with making it possible for him to pursue art, and to now serve as a resource for his work. “It’s a privilege to have parents who support you if you’re in the arts,” he says. “My mom was always a big champion of what I do, that’s sort of why I do what I do, to make her proud after she has invested so much in me and encouraged me. And what better place to learn about who you are and where you came from than your parents?”

He reveals that his painting Sabong, of two chickens in battle, “actually came out of a story [my mom] told me of how they would raise chickens back home. Each of her younger brothers was assigned their own chicken, then a cock fight would happen. It’s sort of a really harsh lesson in morality. I approached that painting in a way that was so foreign to me. Cockfighting is so widely accepted in the Philippines, while a lot of people say they can’t even imagine seeing something like that. So I think it was about understanding that disconnect. It was also an excuse to ask my mom about growing up in Davao.”

Joaquin is the current artist in residence at BoxJelly, where he says you can find him when he is not in the Museum Shop. He has a studio at the back of the co-working space where he is working on a series of portraits, a project he has been wanting to do for a long time.

“Salman’s work has definitely had an influence on the work I’m doing. I think seeing work that felt honest and genuine really inspired me to do something similar. In school, a lot of the work you do has to have a strong conceptual basis to it, some sort of critical aspect. But my first love has always been figurative painting—portraits, people, stories. So in applying for this residency, I was being honest [with my portraiture proposal]. I guess they saw that, too, and granted me the residency. It’s been amazing to talk with people in the community and use those conversations to craft a portrait of them. Usually I’ll hang out, talk with them for a bit and maybe do some sketches and snap some photos and then build the paintings on my own. I encourage people to come and visit.”

The six-month residency will end in December and culminate with an exhibition of the work he has created. As part of the program, Joaquin will teach a portraiture class at BoxJelly’s sister space Fish School.

Joaquin also has work in the University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa Art Gallery exhibition Honolulu New Painting Invitational, on view through Oct. 22. The show includes a lecture series, and Joaquin will give a talk on Thursday, Sept. 28, 1:30-2:30, Auditorium, UH Mānoa Art Building.

Posted by Lesa Griffith on September 22 2023