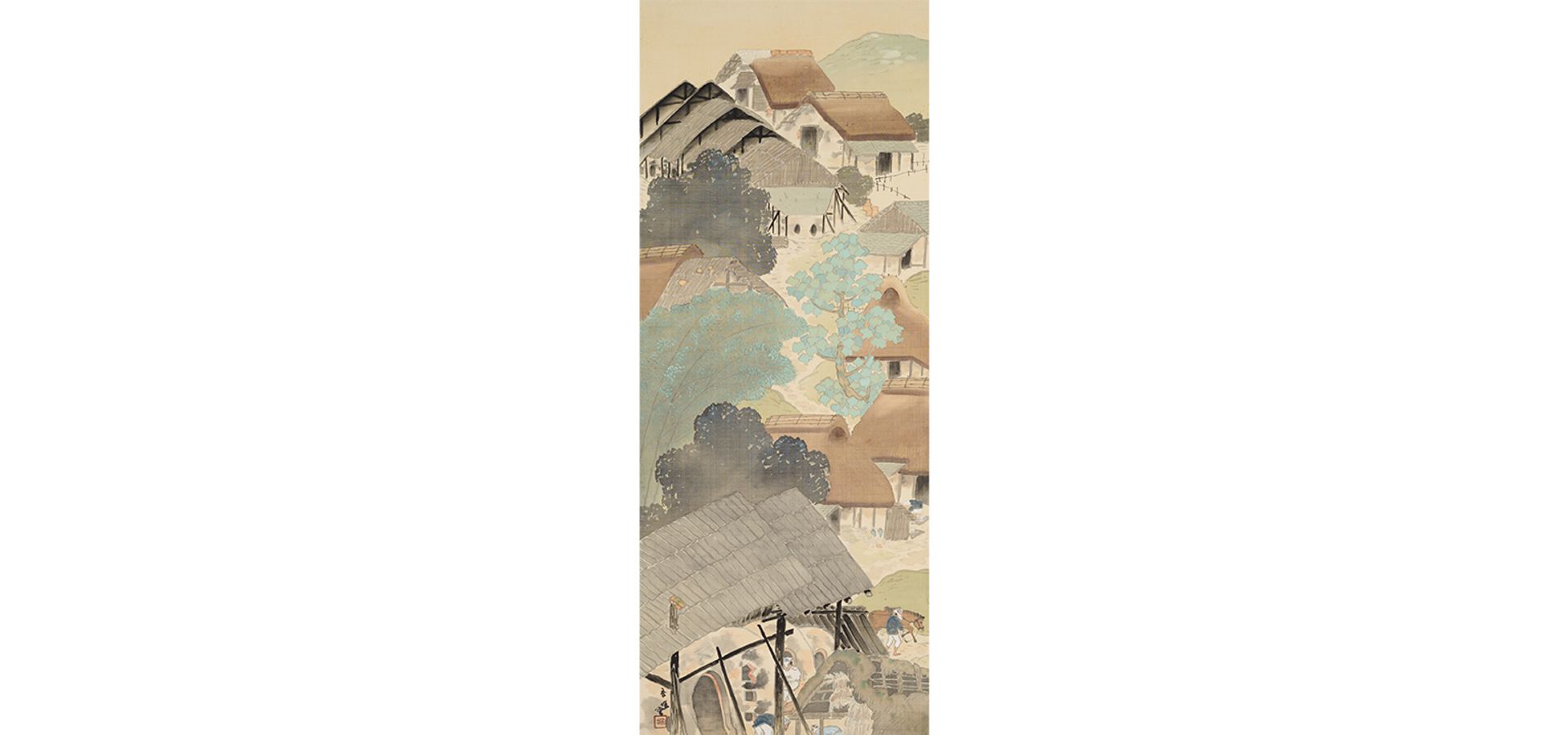

Asami Kōjō (1890–1974)

Scene at a Kiln

Japan, c. 1915

Hanging scroll; ink and color on silk

Gift of Terry Welch, 2021 (2021-03-028)

VIEW HI-RES IMAGE

The Meiji period (1868–1912) brought dramatic changes to traditional Japanese ceramics. Ceramics were identified by the government as having potential for industrialization and export, so modernization of both techniques and means of production was actively encouraged. This resulted in the flourishing of certain types of ceramics, for instance Satsuma ware. Modern Satsuma ware, characterized by complex designs in brightly colored enamels and gilding, received imperial patronage and was given as diplomatic gifts to foreign governments. Technology such as electric kilns facilitated mass production, and soon Satsuma ware was widely exported, becoming synonymous with Japanese art around the world.

At the same time, these technically polished modern ceramics designed specifically for export stood in stark contrast to traditional stoneware, which was largely ignored by the government. As with other aspects of traditional culture, though, modernization ironically resulted in a greater appreciation for humble stoneware, culminating in the Mingei (Folk Art) movement of the 1920s–1930s, which continues to be influential in international aesthetic theory today. Here Kōjō depicts not a modernized ceramics production facility, but rather a traditional village workshop. From the staggered roofs we can identify the kilns as noborigama or “climbing kilns,” traditional multi-chamber kilns built on a slope to allow even firing temperatures.