The Art Historical Precedents of Modern Japanese Comics, Part 2 of 5: Haiga

For Part 1 of this series exploring the art historical origins of manga, click here.

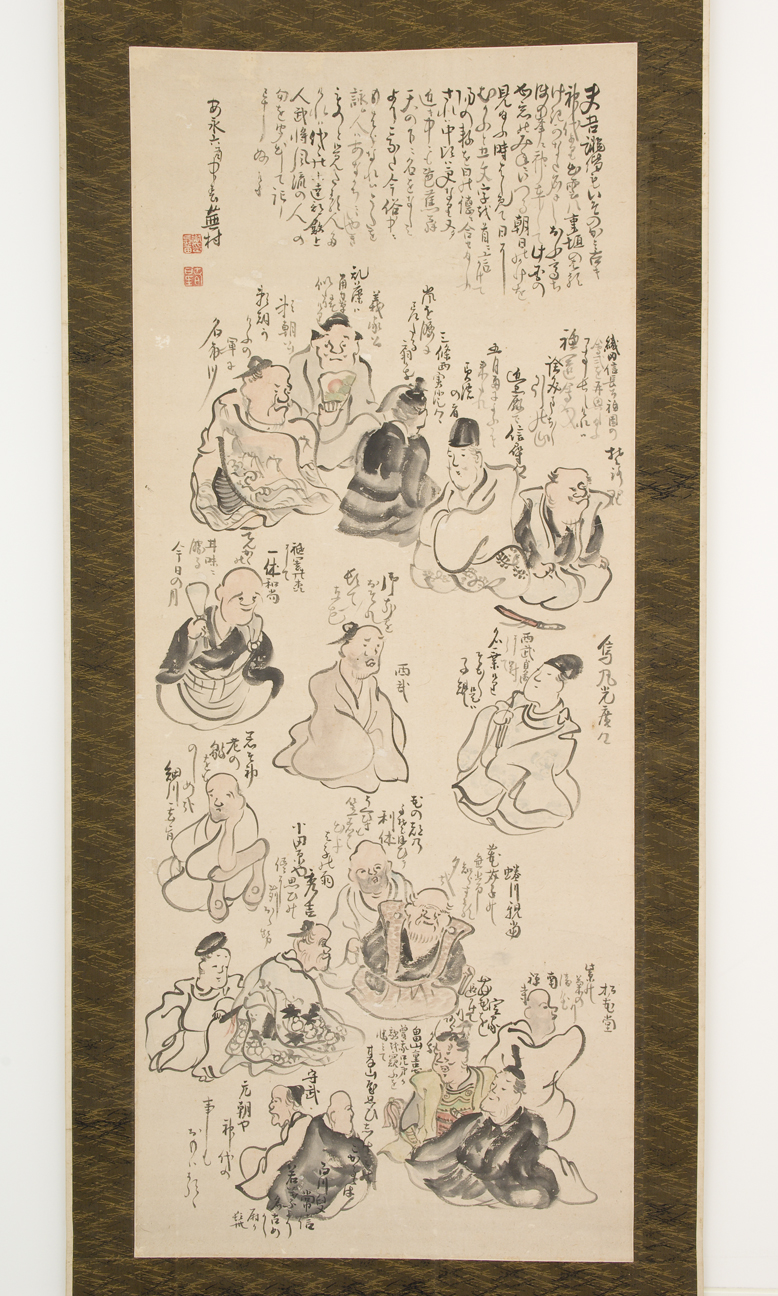

Among the various highlights in the collection of the Honolulu Museum of Art that may have influenced the development of modern Japanese cartoons and comics, a rarely acknowledged gem is Caricatures of Eighteen Poets (1777) attributed to Yosa Buson (1716–1783). This hanging scroll is an example of haiga, a genre of literati painting that discusses poetry—particularly linked verse (haikai ), an expanded form of 17-syllable haiku poetry.

Attributed to Yosa Buson (1716–1783). Caricatures of Eighteen Poets. Japan, Edo period (1615–1868), 1777. Hanging scroll; ink on paper. Gift of Mr. George H. Kerr, in honor of Sir George Sansom, 1958 (2409.1).

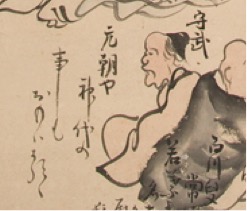

Below a short essay about the historical development of Japanese poetry, the artist has painted portraits of eighteen individuals, and with the exception of a child attendant, each includes a revered poet identified by name and a sample of his writing. In the lower left corner of the composition is Arakida Moritake (1473–1549), the originator of linked verse. This endearing, comical portrait of the author accentuates his jowls and shows his eboshi cap slipping back to reveal his prominent forehead. The calligraphic outline of his robe gracefully leads our eyes to the sample of his poetry inscribed beside him:

New Year’s Day / How it evokes / the Age of the Gods

Ganchō ya / Kamiyo no kotomo / omowaruru

Detail showing the poet Arakida Moritake (1474–1549) and an inscription of one of his poems.

Arakida’s poem references the mythology behind the Grand Shrine at Ise, the sacred Shinto site where he served as head priest in his late years. Dedicated to the sun goddess Amaterasu, the shrine’s inner sanctum is believed to hold the Sacred Mirror, which brings to mind one of the creation myths in the Records of Ancient Matters (Kojiki, c.711). Suffering harassment from the other gods, Amaterasu retreats into a cave, and as a result, the world suddenly plunges into darkness. Desperate for daylight, the deities devise a scheme to lure the sun goddess back out. They hang a mirror from the branch of a nearby tree and, in order to catch her attention, throw a raucous party. When Amaterasu peers out of the cave, she notices her gleaming reflection in the mirror. She finally emerges from the cave to investigate further, and like the dawn of New Year’s Day, the world is restored to light.

Just as Kabuki theater, which developed in the early 17th century, reflected the ostentatious taste of commoners, in contrast to the restrained Noh performances favored by the social elite, the mid-16th century witnessed the popularization of haikai, which, as folk poetry, had a far lighter, more playful sensibility than classical Japanese poetry (waka). In keeping with the simplicity and whimsy of haikai itself, haiga illustrations were painted quickly, and figures were typically sketched with a gestural quality. It’s easy for us to appreciate the influence that haiga paintings such as this, with its playful depiction of Arakida and the other poets, would eventually have upon the development of modern Japanese cartoons at the turn of the 20th century.

Special thanks to Kiyoe Minami for her assistance with researching this painting.

– Stephen Salel, Curator of Japanese Art