The Art Historical Precedents of Manga, Part 4 of 5: Toba-e

For Part 1 of this series exploring the art historical origins of manga, click here. For Part 2, click here, and Part 3, click here.

Describing the state of art historical research in the 1970s, the scholar Ernst Gombrich (1909–2001) wryly lamented, “we have become intolerably earnest….The idea of fun is even more unpopular among us than the notion of beauty.”

Just as comical works, such as those of Geoffrey Chaucer (1343–1400) and William Shakespeare (1564–1616), can be found throughout the history of English literature, works of visual art that display a similar sensibility have been produced for centuries. Only since the popularization of Marcel Duchamp (1887–1968), however, have those works been identified as art-historically important and appreciated within the context of humor. Japanese woodblock prints, woodblock-printed books, and paintings produced before the 20th century are frequent subjects in that new, ongoing conversation.

Although modern cartoons (simply executed sketches) and comics (a series of images, often combined with text, that conveys a narrative) are not limited to works with humorous intent, as the more common definition of the word “comic” implies, early works in those fields were typically intended to be lighthearted. Previous blog posts have described art-historical precedents to modern Japanese manga, including a comical handscroll that dates back to the 12th century. In the early 18th century, Toba Sōjō (1053–1140), the artist to whom that scroll is attributed, was commemorated through the popularization of Toba-e–paintings and prints that emphasize exaggerated body proportions and dramatically gestural poses. Important highlights in this often-overlooked genre include the work of Ōoka Shunboku (1680–1763), Matsuya Nichōsai (before 1751–c.1802) and Takehara Shunchōsai (died 1801).

Toba-e

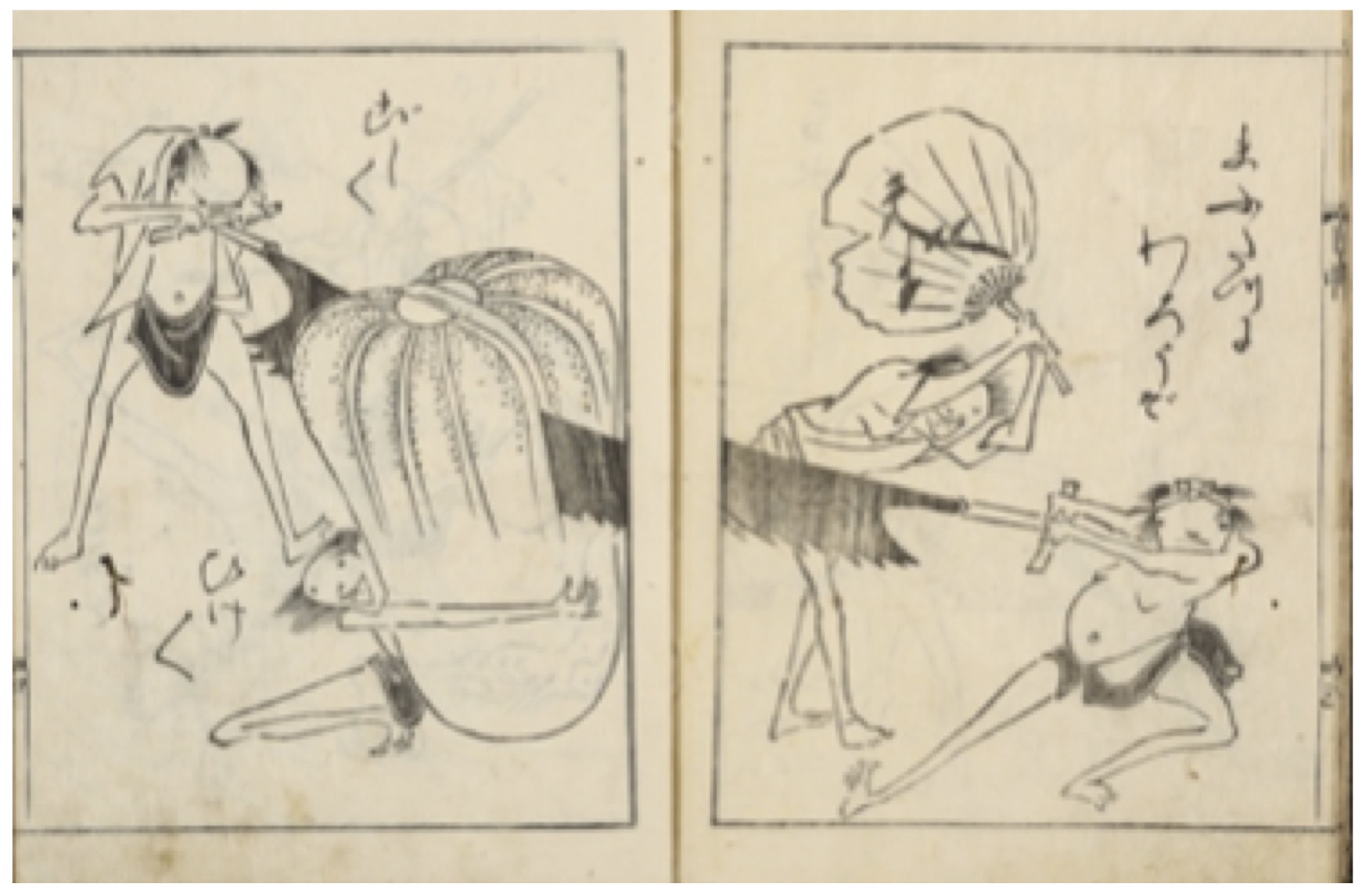

Attr. Ōoka Shunboku (1680–1763). The Toba Carriage, Drawn with a Light Brush. Edo period (1615–1868), c. 18th–mid 19th century. Woodblock-printed book; ink on paper. Purchase, Richard Lane Collection, 2003 (TD 2018-1-047)

The image displayed here, which is attributed to Ōoku Shunboku and which dates to the 1720s, typifies the Toba-e style. It depicts four men in a kitchen preparing to cook a pumpkin. Because of the vegetable’s monstrous size, in order to split it, two men operate a cross-cut saw, a third tries with all of his might to hold the gourd in place, and a fourth cools the other three with an oversized uchiwa fan. Shunboku portrays the characters with the endearing quality of puppets from Jōrūri theater. Their heads are simple spheres with tufts of hair, while their limbs stretch and bend as if made of some sort of elastic material. Inscribed in the blank space surrounding the characters are sound effects and exclamations. The cutting of the saw is expressed in the upper left as “zashi zashi,” and the firm grasp of the third cook is denoted in the lower left as “hike hike.” In the upper right, the cook wearing a hachimaki, a headband symbolizing courage and perseverance, exclaims, “Let’s cut this thing clean in two!” (Mafutatsu ni warō zo!) Frighteningly, no one seems to notice that the third cook’s right hand is directly in the saw’s path, and the impending disaster brings to mind the cringe-inducing slapstick comedy of early 20th-century film stars like Buster Keaton (1895–1966).

Hiroshige

Utagawa Hiroshige (1797–1858). Yokkaichi: The Mie River. From the series The Fifty-three Stations of the Tōkaidō. Japan, Edo period (1615–1868), c. 1833–1834. Woodblock print; ink and color on paper. Gift of James A. Michener, 1978 (17228)

By the mid-19th century, the style of Toba-e had become so popular that even the most celebrated print designers of that generation utilized it. While far more colorful and finely crafted than the monochromatic sketches of Shunboku and Nichōsai, several beloved works by Utagawa Hiroshige (1797–1858) clearly display the same aesthetic. Katsushika Hokusai (1760–1849) is likewise known to have published Toba-e prints. Even in the Meiji era (1868–1912), when Japanese artists began to abandon the traditions of woodblock printmaking, Shunboku’s art was hardly forgotten. George Bigot (1860–1927), a French artist who founded Japan’s first Western-style satirical newspaper in 1882, filled the journal with illustrations, thereby ushering in the next phase in the history of Japanese cartooning. The name of Bigot’s publication?

He dubbed it Tobae.

– Stephen Salel, Curator of Japanese Art